To a seasoned skydiver, the vision of a packed parachute on the back… the open door of an aircraft flying a couple of thousand feet above the ground… and a blast of air hitting the face is like a saucer of cream on the mental horizon of a cat.

The exhilarating feeling is irresistible. A jumper would go as far as one can to satiate the desire to skydive. The Parachute Jump Instructors (PJIs) of the Paratroopers Training School (PTS), Agra are no exception. Drop a pin anywhere on the map of India and in a radius of fifty miles of the pin there will be a place where Akashganga, the Skydiving Team of the Indian Air Force (IAF) would have carried out a skydiving demonstration as a part of a major national event or a military tattoo. If not a demonstration, it would be a paradrop as a part of an airborne military training exercise.

Thanks to my tenures of duty as a PJI, I have been a part of many such displays. From the identification, reconnaissance and exploration of new Drop Zones in the freezing cold Leh-Ladakh region and trial jumps on those Drop Zones, to the exit over the Indian Ocean to land on a target in Thiruvananthapuram, each jump I undertook was different from the other and memorable in a unique way. When I look back, some stand out. An interesting one that often returns to the mind is the one performed as a part of the raising day celebrations of the President’s Bodyguards in November 1998.

I was then the Assistant Director of Operations (Para) at the Air Headquarters.

It was a Herculean task to get the requisite permissions and clearances for the demonstration at the Jaipur Polo Ground. With the who’s who of Indian leadership residing in Lutyens’ Delhi, security was a big concern. Jaipur Polo Ground was not far from the Prime Minister’s Residence. “It would be imprudent to allow such ‘frivolous’ activity in this area,” was an opinion. Then there was the issue of availability of airspace in the proximity of the busy Indira Gandhi International Airport where an aircraft takes off or lands almost every minute and dozens guzzle fuel as they await their turns on the ground or orbit in the nearby sectors. For many well-meaning people, disrupting the air traffic for a skydiving demonstration was an avoidable proposition. An easy way out for those in authority was to say: “NO.”

Notwithstanding what was happening on the files between the Air Headquarters, the Army Headquarters and the South Block in Delhi, the jumpers were agog, drooling. They were excitedly looking forward to the opportunity to jump at the prestigious event to be witnessed by the Supreme Commander of the Indian Armed Forces. Shri KR Narayanan was the then Honourable President of India.

How the permission to undertake the skydiving demonstration came about is the subject matter of another story. Suffice it to say that it did come—somehow. There were caveats, though. We were directed to operate from Air Force Station, Hindan. A team of security experts would sanitise our aircraft and inspect the parachutes for hazardous materials. We were told that they might frisk the jumpers too. Being personally searched was an irksome idea which we brushed aside in service interest. Although the permission had been granted, we were also to await a last-minute clearance from Palam Air Traffic Control (ATC) before take-off. After getting airborne we were to follow a given corridor; report at check points and proceed only on further clearances. The helicopter was permitted a maximum of 21 minutes over the Polo Ground to disgorge the jumpers and clear the area. Would the conscientious security apparatus be obliged to consider the aircraft ‘hostile’ if it strayed from the assigned route, or overstayed its allotted time over the Drop Zone (the Jaipur Polo Ground)? May be. May be not. To us, it mattered little as long as we could jump.

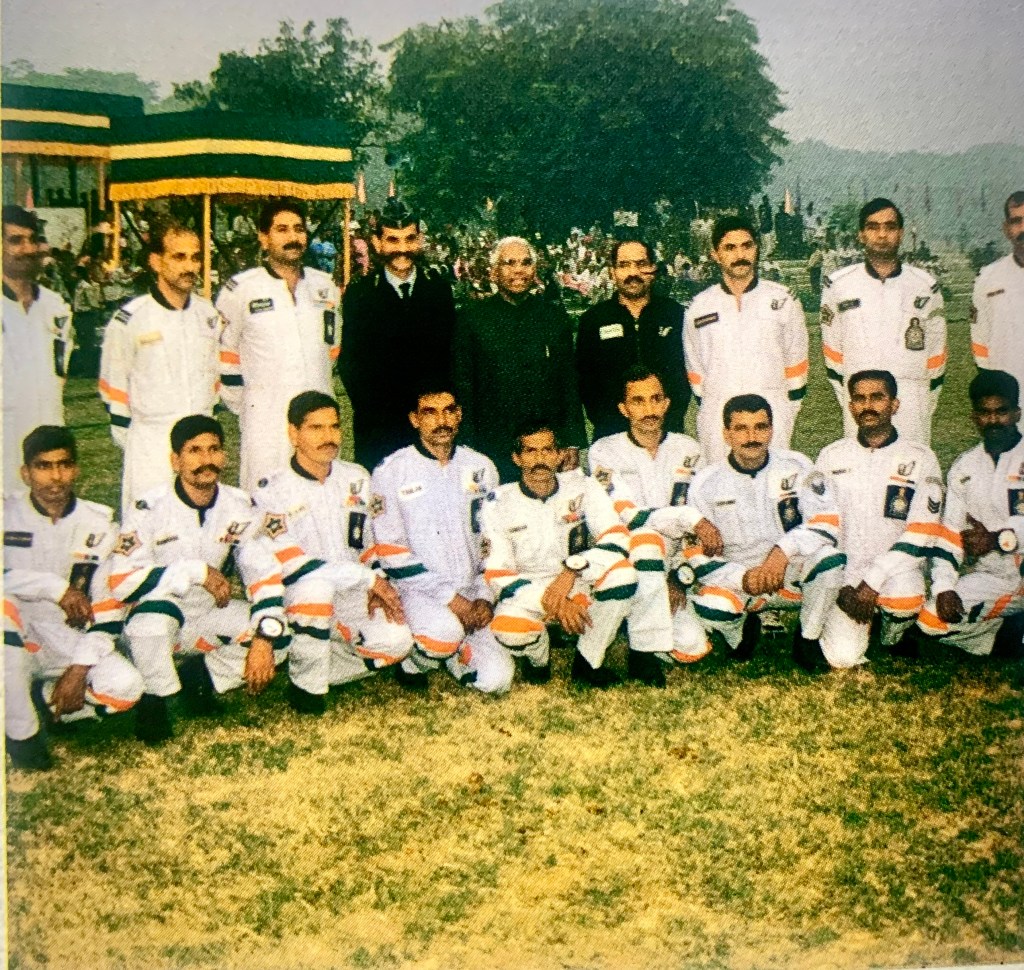

On the D-Day, the team led by Squadron Leader Sanjay Thapar, the then Chief Instructor PTS, arrived from Agra. Group Captain TK Rath, (the Director, Air Force Adventure Foundation), Squadron Leaders HN Bhagwat and RC Tripathi (both of the AF Adventure Foundation), and I joined them at Hindan. We inspected and lined up our parachutes and jump equipment and dispersed, since enough cushion time had been catered for, to account for unforeseen changes in programme. We all had our ways of passing the time available before take-off. Most sat quietly with fingers crossed hoping and praying for the drop to go through, because such VVIP programmes are prone to last minute hiccups. Group Captain Rath immersed himself in a book which he always carried in his overall pocket. He took a break in between to do a headstand. It was his way of attaining peace and calm. Thapar was engaged in communicating with Palam and the controller at the Polo Ground for the updates.

It was “OPS NORMAL!”

Minutes into the break the peace of sorts that prevailed on the tarmac was shattered by a commotion. The Security Team—in civilian clothing—after sanitising the aircraft had started overturning our lined-up parachutes to inspect them. They were alarmed to see sharp knives attached to the straps and had started taking them away.

Squadron Leader Tripathi saw them and literally pounced on them, “What are you doing?” he shouted.

“We are doing our duty… securing and sanitising everything. You can’t jump with these knives.” Their leader said with authority.

“But these knives are our lifeline… we need them in case we have to snap some parachute rigging lines in an emergency.”

“We can’t help it… sharp objects around a VVIP are a taboo,” he drew a line.

Tripathi wasn’t the one to give in easily. He sparred on, “Well, now you have physically handled our parachutes without our knowledge. We don’t know if they have been rendered unfit for use. And, you are not allowing us to carry our survival knives, which is a must for us.” He let that sink in, and then came with the final punch, “Under the circumstances, it will not be possible for the team to jump. Please inform the guys at the other end that the demonstration jump is being called off for these very reasons.”

There was stunned silence before the leader spoke, “We understand your requirements. But you cannot cancel a programme meant for a VVIP and blame it on us. We are all men in uniform. We must find a way out.”

After a little ado, we were permitted to carry our jump knives.

The wait thereafter was long. Panic set in when the clock struck four. It was our scheduled time of take-off. There was no clearance yet. The Honourable President would arrive at 5:00 pm as per programme. In an extreme situation, just in case the Skydiving Demonstration couldn’t be undertaken for any reasons, the Military Band present at the Polo Ground would play martial tunes to entertain the audience. None was interested in that Plan-B; every stake-holder wanted the jump to go through.

In those moments of uncertainty, a deliberate decision was taken to get airborne and hold position over the dumbbell at Hindan airfield so that no time was wasted if and when a go-ahead message was received. So, still on tenterhooks, we strapped our parachutes and boarded the helicopter.

The clearance came 15 minutes too late; we’d now be cutting fine. Our helicopter was asked to hold position over the Yamuna bridge and wait for the final clearance. Time was running out. November smog had begun causing concern. But Thapar, who was born and brought up in Delhi was not deterred by the falling visibility; he knew the ground features by heart. He could manoeuvre blindfolded.

When the final clearance came, there was just enough time to make one pass over the Polo Ground. Under normal circumstances, the aircraft makes three passes over the Drop Zone—one, for the pilot and the Skydiving Team Leader to familiarise with the target on the ground and ascertain the line of run. The other two passes, are to drop jumpers in batches of six to eight each.

A confident Thapar took the decision to do away with the first two passes over the spectators. He briefed the jumpers in the aircraft that all of them—more than a dozen—would exit the aircraft in one go. He re-assigned the parachute opening heights to each jumper and stressed the need to stick to it else there would be many jumpers approaching the landing area together resulting in a melee; maybe collisions.

Good things don’t come easy!

At 5:00 pm, when the helicopter came overhead, the Drop Zone Safety Officer informed that the President had not arrived. “Please hold on!” he advised.

Three minutes later, the Air Traffic Controller from Palam Airport instructed our helicopter to clear the area instantly; international flights were getting inconvenienced. It was when the captain of the aircraft was contemplating abandoning the mission that Thapar leaned out of the aircraft and spotted the President’s motorcade. It would still take a couple of minutes to reach the spectator stands. When he turned back, he had taken the decision.

“Go!” he commanded the line of jumpers awaiting his instructions. Within seconds all the jumpers were out of the helicopter.

The pilots racing back to Hindan airfield saw the colourful parachute canopies adorning the sky over Lutyens’ Delhi. The Honourable President’s motorcade just moved into the Ground as the skydivers began landing one by one. It turned out to be a bit comical when the jumpers responded to the tune of the National Anthem and stood to attention on touchdown.

Cancellation of a para drop is one of the worst possibilities faced by a Parachute Jump Instructor.