About a myth called indispensability.

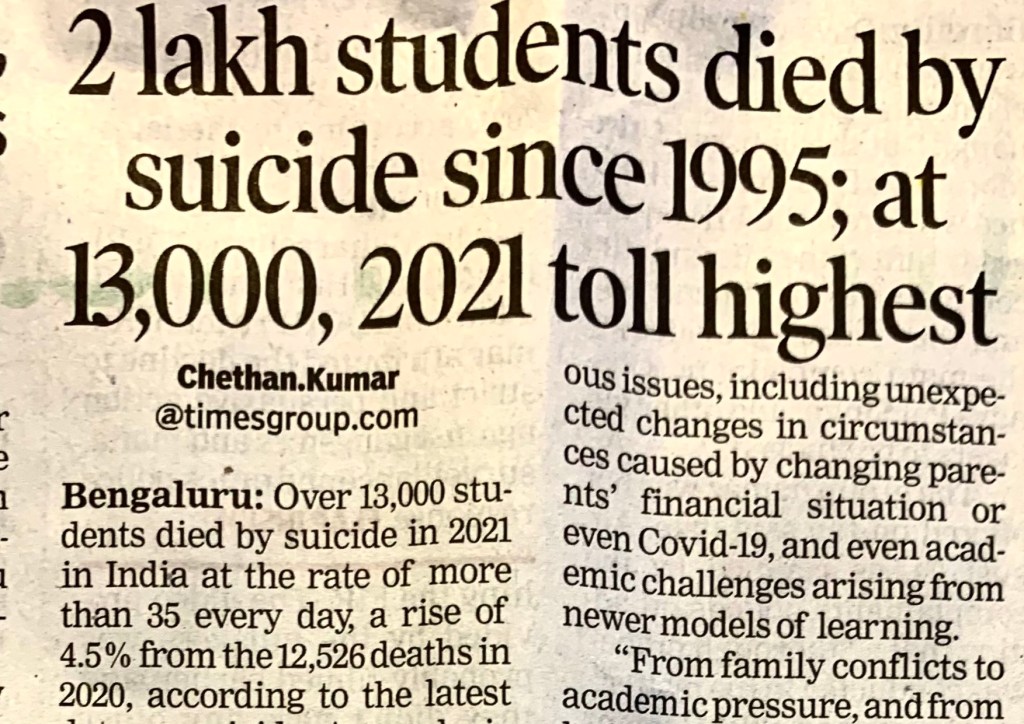

Remembering dates and recalling chronology is not my cup of tea unless they are associated with memories. Suffice it to say that the exotic east was my home for two and a half years around the time 9/11 happened. Chhaya, my soulmate and Mudit, our son had stayed back in Delhi for the latter’s schooling when I moved on a posting to Tezpur as the Senior Logistics Officer (SLO). Those days mobile phones were rare and smart phones, non-existent. Video chat existed, but only in the drawing room discussions about the awe-inspiring future technologies. Public call booth was our means of connecting with our dear ones back home. The waiting at the booth used to be long when the call rates used to dip after 10 pm. Despite those little struggles, one realises in hindsight that without smart phone, existence was meaningful—one could indulge in activities which boosted the feel-good-factor, and to some extent, the quality of life.

In Tezpur, without family—people called that state of being, forced bachelorhood—I could devote all my time and attention to work. Thanks to the dedication of my predecessors, logistics support to the Station was streamlined; the ageing MiG-21 fleet was afloat, nay soaring. So, I also had the time to afford other activities. Once in a while, critical shortages of spares, or elephants rampaging our Ration Stand, used to inject excitement in our routine.

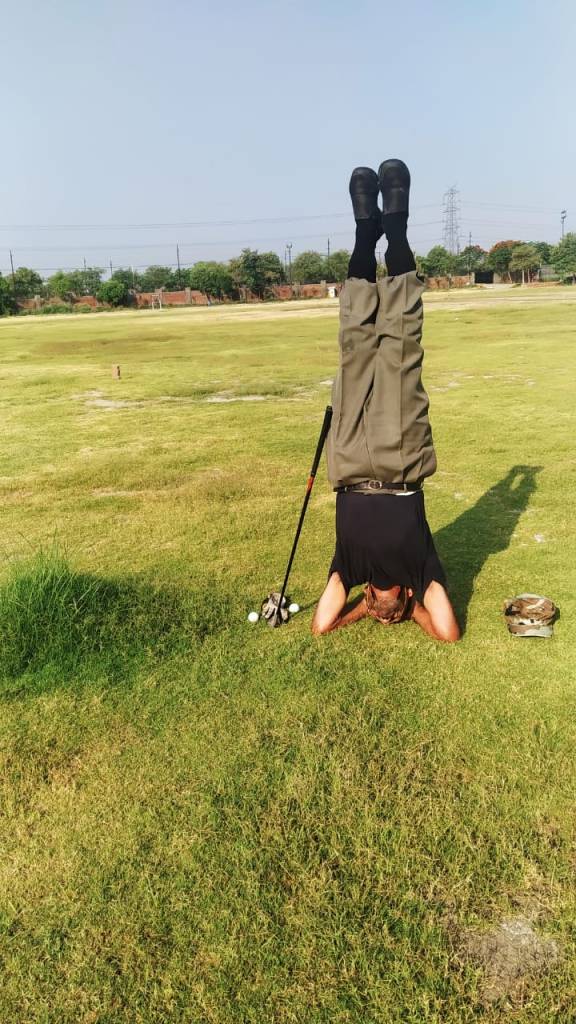

The Gajraj Golf Club situated across the runway, offered me an opportunity on a platter to sharpen my golfing skills. My approach to the game was maniacal. I played like a man possessed, not missing a day unless there was a justifiable good reason. Unbelievable, but true—I played 45 holes on a particular holiday. That fact must not mislead one to conclude that I was playing well—piling birdies and pars. Far from it, long hours spent on the fairways—not to talk of the golfing lessons from the pro, Minky Barbora—did little to help me master my shots. At my best, I played to a fourteen handicap. So be it. I was happy playing. Period!

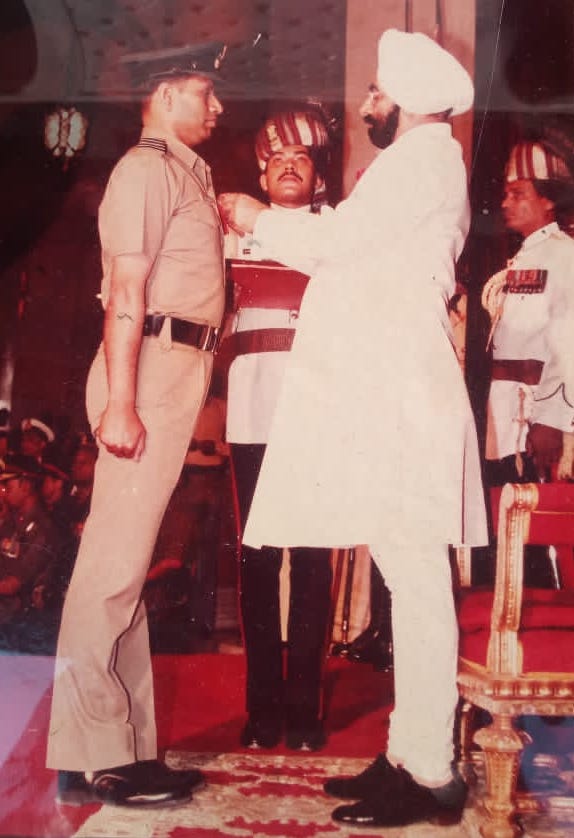

Air Commodore PK Barbora, popularly known as Babs Sir (later Air Marshal and Vice Chief of the Air Staff) was our Air Officer Commanding (AOC). He, and a dozen other officers shared similar passion for golf.

The weather in Tezpur used to be hot, and mercilessly humid, for most part of the year. Rest of the time, it used rain heavily. A drizzle could never stop us from teeing off. What about rain? It was a mutually agreed rule to continue playing if it started raining after we had teed off. We permitted ourselves free lateral drops whenever a downpour created scores of shallow lakes in the fairways. We were unstoppable. For a few minutes though, we paused our game one day, only to give way to a herd of about 30 to 40 wild elephants who chose to cross our path.

Rounds of golf on the courses owned by the association of tea planters were jamborees. Amusingly, their fairways were maintained by the grazing cattle. The events provided unadulterated joy, taking us to the next higher level of being. Nirvana!

Indulging in a sporting activity alone, golf in particular, is no fun. Normally the AOC used to telephone one of us and confirm if we were playing on a given day. One day when others were occupied, he called me to check, if I was available. “So Ustaad, are we ON today? What time do we tee off? Is 2:45 fine?”

“Ustaad!” That’s how the AOC addressed everyone. That form of address had nothing to do with the formal term coined by Air Chief Marshal S Krishnaswamy to recognise and honour professionals.

It was a matter of chance that I too had a commitment that day. So, I responded apologetically, “Sir, I have a commitment today… I might get late. May I join you on the third or the fourth tee?”

“Ustaad, are you trying to impress me by staying late in the office.” Although the AOC said it in a lighter vein, his remark pricked me. Oblivious of my hurt feeling, he chuckled, “It’s fine. I’ll start alone. See if you can make it after finishing your task at hand.” Was I attaching too much meaning to the AOC’s words? Was I inviting offence when it was not meant? I wasn’t sure. But disturbed, I was.

The AOC was on the third tee when I joined him, “Good afternoon, Sir.” A grumpy me greeted him half-heartedly. His words, “Are you trying to impress me…,” were still screeching in my cranium; disturbing me. I felt he had been unfair in judging my commitment to work as an exercise to impress him. I knew in my heart, I would work anyway, regardless of him.

The AOC must have read my mind for he broached the subject, “Good afternoon Ustaad. What were you stuck with?”

“Sir, the weekly courier was to land today. I had a repairable aeroengine to be sent to Bangalore… it was urgent. Sometimes, when the aircraft are loaded to their capacity, the loadmasters decline our consignments. I went to the tarmac because I didn’t want that to happen today. Fortunately, they had the space and accepted our load.”

“What would you have done if they had had no space to accommodate your stuff?”

“It is a common occurrence, Sir. When there is no space, I speak with the crew of the aircraft and try to prevail upon them to offload some of their less important packages and accept my critical stores. I promise them to dispatch their offloaded packages by the next available aircraft. They appreciate the logistics needs of a fighter flying training station and generally concede to logic even if they are inconvenienced.”

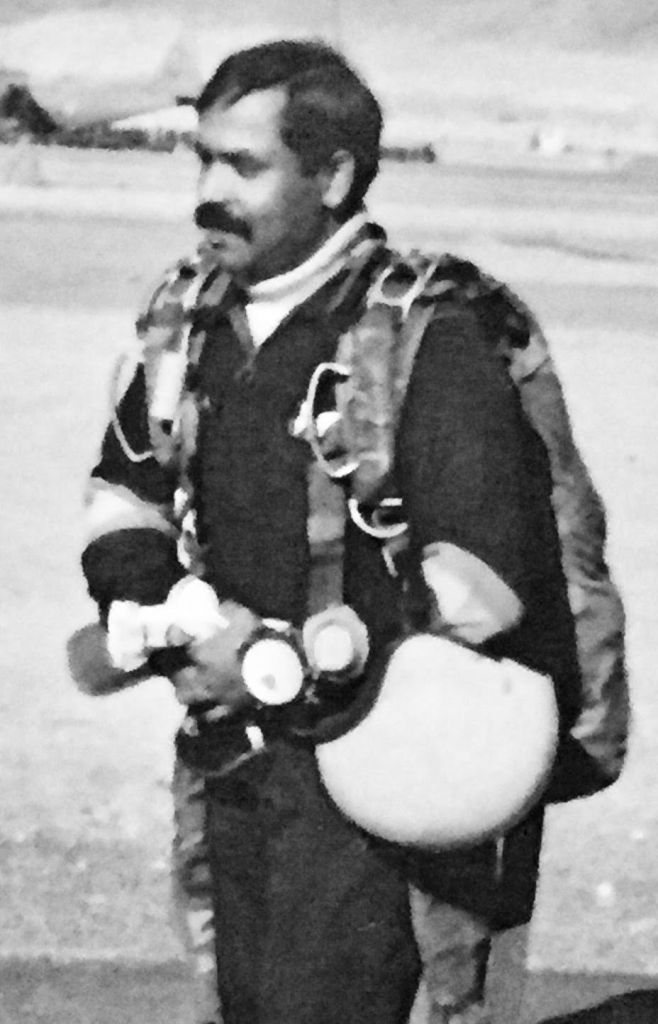

I kept emptying my mind, “Besides, having spent seven years at PTS (Paratroopers Training School) Agra, I am able to connect well with most of the AN-32 and IL-76 crews, and sometimes I am even able to pressurise them to accept my consignments….” The AOC listened to my monologue without saying a word except for an occasional, “Hmm!” I wondered if I had been talking to a wall. We walked the distance together as I kept illuminating my late joining.

On the next green, the AOC was the epitome of peace and calm when he took stance for a long seven-foot putt for a par. The clinking of his Titleist Pro V ball as it fell into the cup was music to the ears. Then it was my turn. About three feet from the cup, with two strokes in hand I was sitting pretty for a birdie. Chaos and disorder were still stewing in my mind when I struck the ball. I missed the putt twice. It was a bogey.

“Oh no! Ustaad, how could you have missed that sitter,” Babs Sir exclaimed.

I shrugged my shoulders in disbelief. I too thought, at least a par was unmissable.

It was a disastrous day for me on the course. When we sat down for the usual cup of tea after the game, the AOC took out his pouch of tobacco and rolled a cigarette. He carried forward the conversation as he struck a match to light it, “You know Chordia, I am a happy AOC who has a conscientious SLO like you working for him. I appreciate your sincerity of purpose. Full marks….” He showered lavish praise on me for despatching the aeroengine. His demeanour suggested that he was headed elsewhere.

“But, think of it. Couldn’t any of your youngsters, or a Warrant Officer, or a Sergeant, have accomplished what you did… simply despatching an aeroengine?” He asked me as he took a last long drag on what remained of his little cigarette.

“Ustaad,” he continued, “Your men are an asset. Good grooming will enable them to shoulder greater responsibilities, and thereby relieve you to devote your time and energy to intellectual work. With thoughtful delegation one can manage things better. The opportunity to golf could be the spinoff of good management.”

I accepted the pearl of wisdom with humility. “Sir,” was all I said in my acceptance speech.

Postscript

There was much substance in what the AOC said that day. My fear that my men would not be able to accomplish things was holding me back from giving them responsibilities and making me feel indispensable. A little introspection and some fine tuning did wonders for me. Thereafter, I had a lot more time. I could not only play golf but pursue a lot of other hobbies and activities. I could immerse in books, draw caricatures, analyse handwriting, practise calligraphy strokes and even try my hand at wood carving. Tezpur turned out to be a greatly satisfying tenure, professionally and personally.

To conclude the sum and substance of this piece, a word about gandak will be in order.Gandak is a canine species, kind of a sheepdog found in Rajasthan. It can be seen walking in the shadows of the camels or under the carts drawn by them. Regardless of the weather—scorching heat or bitter cold—the long tongue of this little beast is always hanging; it is perpetually panting. My mother used to say, a gandak pants because it thinks that all the load is on its back and that it might tip over if it shrugs (read, “shirks”). Hidden inside us is a gandak which gives us a false feeling of indispensability. My life changed when I got rid of the gandak in me.